Because of the nature of my work, I often find myself in the company of children and teenagers. If one intends to write for young adults, or those peeking over the wall into young adulthood to see what the fuss is all about, one finds benefit by listening to them, conversing with them, and generally just taking a softly tipped stick and poking about in territories you might not normally be invited into.

Curiously, that same ‘nature of my work’ is growing more challenging as it does not fit into the current timeframe of many young adults’ attention span—a trajectory of current evolution where now every fleeting second of focus counts and best be saturated with impactfullness.

Where I used to describe the concept of story to young readers as a richly developed plot with engaging dialogue, a diverse set of problems that might tangle complexly at first but unravel beautifully in the end, and a few solid examples of struggle, failure, perseverance, and finally success, now my definition has been forced to change. Currently, I define story as “Once upon a time there was a guy, he had a problem, he figured it out, the end.”

Much more TikTok, much less time-honored tale.

Short-form episodes are now the norm. One can see information streamed about nearly anything and those sessions require a mere 15 seconds of focus. The problem is, is that a recent study determined that the average human attention span has fallen from 12 seconds in 2000 to a whopping eight seconds today.

Goldfish have a better chance of making it to the end of that video as they are believed to have an attention span of at least nine seconds.

Somehow, our youths are being encouraged and pushed to find satisfaction with a story that lasts less time than we expect them to be standing in front of a running sink, washing their hands. I grapple with this especially hard when I realize that oftentimes just one of the myriad sentences I shove into a paragraph far exceeds the newly allotted timeframe many kids will devote to scanning words across a page. And how does one cram a beginning, a middle, and an end into a curt and clipped few moments?

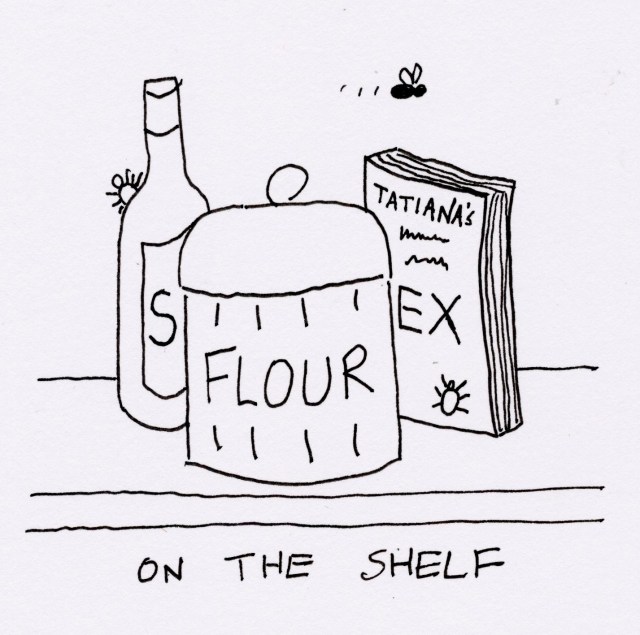

One of the most difficult tasks authors—or anyone with something to sell—must do, is create a pitch. Something that answers Why should I devote my attention (or hard-earned pennies) to you? It often involves boiling your story or your product down to its bare bones—the skeletal structure that shows all strength and no fluff.

The process for authors often happens like this:

- take a 325-page book and reduce it to one page (hard)

- take that one page and tighten it to one paragraph (ugh)

- take that one paragraph and shrink it to one sentence (facepalm)

If you’re writing a film script, the next bit is to slash it to fit the form Blank meets Blank. Godzilla meets The Godfather, Dirty Harry meets Harry Potter, Jaws meets The Little Mermaid—or something like that. Somehow the mash-up is supposed to bring immediate clarity to anyone hearing the phrase as to the plot, struggles, and triumphs within the storyline.

But does it really?

Can one short phrase really tell us the necessary amount needed to exclaim, “I get it”? Can a fifteen second video really reveal the depth of dance, comedy, or education? Is it even possible to jampack a “How to Fold a Fitted Sheet” into 30 seconds or “The History of World War II” into a three-minute YouTube video? Will our next generation of surgeons learn how to remove our gall bladders via Instagram stories?

Personally, it takes me donkey’s years to learn anything. And it’s not because I’m slow. It’s because I’m slow and stubborn. New information that crosses my path is met with skepticism until I can research its source, decipher which end of the political spectrum it may live on, and see Anthony Fauci demonstrate it at a White House Press Conference. It took me literally decades to watch the series MASH because I believed, like the execs telling the show’s writers, that the series run would be limited because the Army isn’t really a pool for humor.

I need convincing. I need repetition. I need my children to walk through the door at holidays and declare amazement at the fact that they’ve actually time traveled into history and perhaps I should let someone in the science department know that it’s possible.

“When are you going to get a new microwave, Mother?”

“As soon as I’ve researched all the newfangled ones on the market. There’s a lot to learn and compare.”

“Have you yet learned that this antiquated piece of junk is a fire hazard?”

“DON’T TOUCH MY RADARANGE!”

But it’s more than just diving deeply into any subject to learn its function, purpose, and capability, it’s also about staying with something long enough to feel the comfort of its complexities. Typically, you cannot learn to play the piano by just watching someone else on video, and it’s downright impossible to sum up our planet’s horrific battles by declaring into a camera lens, “Humans fight. War bad”. There is nothing wrong with embracing the depth and breadth of any subject, but I feel it’s wrong to lead kids into believing any topic can be shortened into a framework of explanation that would have the writers of Cliff Notes blush at its brevity.

Our world is huge in scope and requires effortful thought to make sense of even its least complicated aspects. It’s a daunting task, and we’ll never finish it, but we certainly shouldn’t allow our children to shy away from it. History takes time to be explained. Skills take time to be acquired. Stories take time to be told.

Perhaps we can quote American author and keynote speaker Michael Altshuler more often to our children: The Bad news is time flies. The Good news is that you’re the pilot.

~Shelley

For the time being, the blog is closed to comments, but if you enjoyed it, maybe pass it on to someone else. Email it, Facebook it, or print it out and make new wallpaper for the bathroom. If it moves you, show it some love and share. Cheers!

Don’t forget to check out what’s cookin’ in the Scullery and what we all gossiped about down in the pub. Or check out last month’s post and catch up.